Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: This podcast is a collaboration between costart and Touchstone Productions and the Dads from the Crypt podcast.

[00:00:06] Speaker B: The point is that numbers are maps, and within numbers, is there an underlying secret to the universe? That is the premise of this particular presentation.

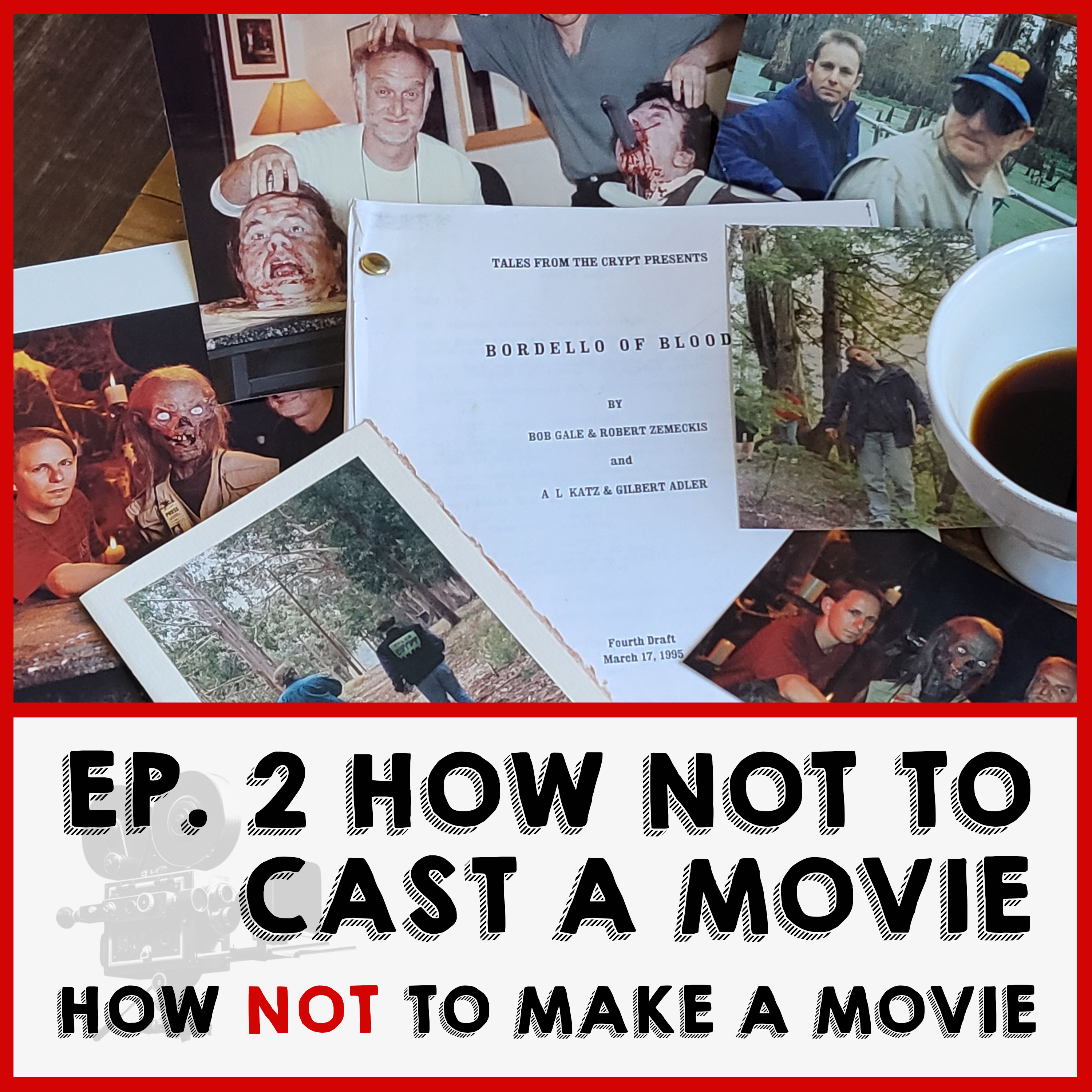

[00:00:21] Speaker A: Hello, and welcome to another episode of the how not to make a movie podcast. I'm Alan Katz. Gil will join us shortly.

You know how you meet someone on the set of a movie, like tales from the crypt presents demon Knight, and the first thought that hits you after, wow, he's a nice guy. Is. Wow, the guy is really smart, too. Well, being smart, especially that smart, has a lot of the same hallmarks as being nuts. Those kinds of people tend to focus with manic intensity on things, and when they do, they kind of look like they know things no one else does.

Yeah, that, too, is what it's like meeting and knowing Charlie Fleischer. Most people know Charlie as the voice of Roger Rabbit.

[00:01:07] Speaker B: Please, ro, I can give you stars. Just drop the refrigerator in my head one more time. Roger, on your head 23 times already. I can take it. Don't worry about me. I'm not worried about it.

[00:01:17] Speaker A: You.

[00:01:17] Speaker B: I'm worried about the refrigerator.

[00:01:19] Speaker A: But that was hardly Charlie's first time at the rodeo. Since the 1970s, he's appeared regularly in human form as an actor and stand up on tv and movies. But Charlie Fleischer is way, way more than just an actor and comedian. He's a renaissance person who paints, creates music, and writes scientific papers. We'll get into all of that as we try and answer the question we posed in the episode's title. Is Charlie nuts, or is he just smarter than everyone else? You be the judge.

[00:01:53] Speaker B: I'm glad you guys got back together. You know, it's. A lot of people thought that Oasis would get back before you guys.

[00:02:00] Speaker A: I had my money on the Beatles.

[00:02:03] Speaker B: That's going to be a different parameter.

[00:02:06] Speaker A: One way or the other.

[00:02:07] Speaker C: He had his money on the Beatles, and some of them are dead.

[00:02:11] Speaker B: I'd say two. Yeah.

[00:02:13] Speaker A: You started in DC.

[00:02:16] Speaker B: Well, I saw. I was born, yeah. But, yeah. Have we started officially Ed, or we're just.

[00:02:23] Speaker A: We have started. This is it.

[00:02:25] Speaker B: This is it.

[00:02:26] Speaker A: This is it, man. We just start talking, and whatever the fuck happens, happens.

[00:02:30] Speaker B: Well, last time I saw you was at Todd Masters, right?

Yeah.

[00:02:34] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:02:35] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:02:36] Speaker A: It was a screening of. Oh, was it a Todd studio or was it at a screening of something?

[00:02:40] Speaker B: This was in Pasadena, that I recall. It was a demon.

[00:02:45] Speaker A: Yeah, it was a demon night screen screening. Yeah, that's right. We bumped it was a demon night screening.

[00:02:50] Speaker B: He had a party. Yeah, he had, he had a corner.

[00:02:54] Speaker A: That's, that, that's right.

[00:02:55] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:02:56] Speaker A: It was. And it was great to bump into you there. It really was.

[00:02:59] Speaker B: Yeah. Any kind of bump is good as long as it doesn't involve insurance.

[00:03:04] Speaker A: Sure.

Though we've worked together, I had no idea that you were science and that you had this whole scientific side to you. I mean, I guess if I spent, if we had more time on the set talking, maybe I'd learn that.

[00:03:21] Speaker C: But see, I remember a little of that. I remember having a conversation with you while we were shooting about that and asking you a little bit more about when you say you're interested in science, what exactly does that mean? And I remember, you know, I remember we started talking about that a little bit and I just was sort of, wow, this guy is really an interesting guy to talk to. Forget the acting and forget the motion picture stuff and forget tales from the crib.

It was really exciting just talking to you about stuff.

[00:03:52] Speaker B: Well, I'm part scientist and part artist. So the artist wakes up and says, wow, it's a beautiful day. And the scientist part goes, yes, but how does it work?

[00:04:04] Speaker A: Now when you, as I said, you started in DC and then your first, as you jumped out of the nest, your first goal was medical school.

[00:04:16] Speaker B: Well, I thought I was going to do that before I really entered college just as a child growing up. And there are friends of my parents that always address my birthday card to doctor Charles Fleischer. You know, it's kind of a temple jewish boy. You should be a doctor. What are you going to do? Be an actor? What are you crazy? So, but I always have had a love of science and scientists and I have in patented inventions. I have a paper on origin of gamma ray bursts on the.

[00:04:49] Speaker A: We will come to all of this because I really, hey, any fan of string theory is a friend of mine.

[00:04:56] Speaker B: Well, I'm not sure about string theory. It's not provable.

[00:04:58] Speaker A: But still, it's a fascinating topic.

[00:05:01] Speaker B: It's the, anytime you get into the quantum world or subatomic, it's interesting.

[00:05:07] Speaker A: The idea that something can come from nothing is enthralling. And in quantum, quantum mechanics that can.

[00:05:16] Speaker B: Happen so long as I don't know if there is such a thing as nothing.

[00:05:24] Speaker A: Well, that is, that is a whole, that's a whole conversation unto itself. The something versus nothing. One of the things that, that I find rather compelling about string theory is that in string theory there's no beginning and there's no end.

[00:05:43] Speaker B: Well, once again, words can be tricky, but I think everything is cyclical, and the universe that we are in right now will one day no longer be.

[00:05:58] Speaker A: And then.

[00:05:59] Speaker B: And just, you know, just look at any aspect of life will parallel, recapitulate others. Ontogeny recapitulates. Phylogene was like that. So, you know, our lives, we. We live and then we die, and the universe lives and dies, and then something else goes on again. It's.

[00:06:15] Speaker A: Exactly.

[00:06:15] Speaker B: So we're part of it. That's the. That's the essential wonder for me, that we're part of it all. The unfolding of this magic.

[00:06:23] Speaker A: What. What changed your direction from medical school? Then you headed to Chicago, you went to Goodmande, right.

[00:06:31] Speaker B: Well, when I was. I mean, I always had been, you know, doing shtick, and I love Jonathan Winter's groucho. And then at Southampton College, I was in a couple of plays, and I did well in them, and I really loved doing it. And then I went and auditioned at Goodman, and I remember my parents told me they did some research and said, you know, only 3% of the people that are in the active skill work. And I said, great. Out of 100, I'll have two more people to talk to.

So, yeah, I've always had many directions. If you want to picture a bicycle wheel, this center there is the hub. The spokes appear to radiate outward in different directions, but they all end up with the wheel. So it's kind of like me. Like, I go this way, then that way. But, you know, you go to the wheel and you see it all come together. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:07:29] Speaker A: It happened for you fairly quickly in the seventies. You got some tv gigs.

[00:07:36] Speaker B: Yeah, when I first came out, I started working, I think, welcome back, Cotter. Cotter. Yeah, sure, Cotter. Yeah, you got it.

[00:07:44] Speaker A: Oh, but you had.

Was that a regular part? You were Carvelli, you were Choco, Laverne and Shirley.

[00:07:54] Speaker B: That's correct as well.

[00:07:55] Speaker A: God, then you even were on laughing.

[00:07:59] Speaker B: That was my first gig. That was before I even moved out here. I came out here from Chicago on a vacation, just to explore. And then I saw red Fox at the comedy store, and he said, you know, cigarette. Got him a cigarette. And then he said, NBC. And I went to NBC just to look around, and I ran into Paul Keys, I think, the producer of laugh in, and interestingly enough, Alan Katz. The other Alan Katz.

[00:08:27] Speaker A: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:08:29] Speaker B: Allen Cats and Don Rio. And he was a writer on laugh in, and I had my comedy paraphernalia. Used to play these instruments that I had invented, the teutonaphone and the tattoo phone. And they made. I was a discovery of the week. That was the name of the little bit.

[00:08:47] Speaker C: I was friendly with Allen Katz as well.

And.

[00:08:50] Speaker B: Katz. You're referring to the other Alan Katz?

[00:08:53] Speaker C: Yeah, a long time ago.

[00:08:54] Speaker B: A long time ago. Wait. Great writer. Had great shirts and his sister Phyllis. Cats.

[00:08:59] Speaker A: Yeah. It's funny, when I first got to town in 1985, I had a script called. I forget what he was even called, but I was.

[00:09:08] Speaker B: It called.

[00:09:10] Speaker A: It was called down to earth.

[00:09:12] Speaker B: Down to earth.

[00:09:13] Speaker A: It was called down to earth. Nothing ever came of it. Nothing ever came of it, but people liked it. And so 1985, I had a friend who'd become an agent at William Morris. And so she was my agent. She was sending me around. And among the people that I bumped into was Gil. But I went into a bunch of meetings where I would sit down and I'd start the meeting. And the other Allen Katz, at that particular point, had just put out a script as well. And his was called the hunchback of UCLA.

[00:09:43] Speaker B: Right. He was in it, too.

[00:09:45] Speaker A: When they ultimately made it. It was made as big man on campus. But before that, when it was, he was still out and about. And I would go into meetings, and I'd sit down and go, hi, Alan Katz. Nice to meet you, Alan. And they'd go, we just gotta tell you, we love your script. The hunchback of UCLA. And the first couple of times I was stupid. And I'd go, oh, that.

That wasn't me.

[00:10:08] Speaker B: Right? Take the game.

[00:10:09] Speaker A: Then there'd be this painful silence in the room as they realized they had the wrong Allen Katz. And. Yeah. And then finally I'd say, yeah, I had this script called. And they'd go, oh, yeah, we read that. Yeah, that was good, too. And, you know, then I finally got wise after a couple of meetings, and they'd say, hey, we love the hunchback of UCLA. And I'd go, why, thank you very much. And I think you'll love this idea that I'm about to pitch you just as much as that.

[00:10:34] Speaker B: Sure. That works.

[00:10:35] Speaker A: So I did get his residual checks from time to time. I did not bank them. I will say that.

[00:10:43] Speaker B: I hope not.

[00:10:44] Speaker A: One of the first things I did when I moved out here is I took a groundlings class, and my teacher.

[00:10:50] Speaker B: Said, gary Austin.

[00:10:53] Speaker A: At the ground was Phyllis. My teacher was Phyllis Katz.

[00:10:58] Speaker B: Oh, really? Oh, Gary Austin started that, I think.

[00:11:02] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, it was. It was a great class. I enjoyed it immensely. But it was very funny that it just how it came full circle because, you know, of being confused with Allen Katz by day and then going and taking class with his sister by night. And she was a terrific teacher. I enjoyed that class immensely.

[00:11:21] Speaker B: Yes. Our other Charles Fleischers, I've never met any of them, but I've always wondered what it'd be like to get 2030 people that all have your same name and just put them in a room. And just what kind of dynamic would occur when that similarity is there. It's kind of random and slightly abstract, but, hey, Charles Fleischer, like, if all your friends had the same name as.

[00:11:44] Speaker A: You, it's really annoying. I can tell you. At the same time that this was happening with the other Allen Katz, there was a third Alan Katz, who was trying to break into the business. And he wanted to have a whole club of us where all the Allen Katz's would get together and.

[00:12:02] Speaker B: Yeah, well, that's. We're hitting on that same kind of.

[00:12:04] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And I.

[00:12:06] Speaker B: How many names are available on the earth, you know, unless you're naming kid a, one non trogla.

[00:12:13] Speaker A: You're. You're so lucky to be Charlie Fleischer.

[00:12:17] Speaker B: I really. I had no choice. But I do feel blessed and dressed great and grateful, well read and ready. Give.

[00:12:27] Speaker A: Gil Adler is better than Alan Katz.

[00:12:30] Speaker C: Well, I had a similar problem, though. I was producing a play in New York called El Grande de Coca Cola, right? Very successful play. And one day I get a phone call, and I answer the phone in my house, and the guy goes, is this Gil Adler? I go, yes. I said, who is this? He said, this is Gil Adler. I said, excuse me? He goes, my name is Gil Adler. I've been getting a lot of phone calls, and I think they meant to call you. Do you have something to do with theater in New York? You have a play running? I go, yeah. So he was an attorney on Wall street. We met for coffee one day. He was probably about ten or 15 years older than me, but it was really amazing. I mean, we chatted, we talked. He gave me all my information that he had gotten collected from people who were trying to reach me. And then every once in a while, like once a year, he and I would meet for a coffee, and then we lost track of each other. But it was getting a phone call.

[00:13:21] Speaker B: Like that, saying hi and just bringing it back to now. I think as far as backgrounds today, I think Gil wins for the best theatrical background. He's got a real nice kind of symmetry and perspective. Going. So I will commend you on that.

[00:13:38] Speaker C: Well, I thank you. But if you look more carefully, you'll find it's not so.

[00:13:44] Speaker B: A little bit green screen anyways.

[00:13:45] Speaker C: A little bit more fucked up than normal.

[00:13:49] Speaker B: That's even better.

[00:13:50] Speaker A: You did the Carson show?

[00:13:54] Speaker B: Yeah, I did it several times.

[00:13:56] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:13:58] Speaker B: With Johnny, and then I did panel.

[00:14:04] Speaker A: How many times did you appear before you got panel?

[00:14:07] Speaker B: Oh, I think it's only on it twice. Is that right? Maybe, yeah, twice. So, you know, I did it the first time, and then I did stand up again, and then I went over and I did Moleads the second time. And I remember talking to Johnny about that in the commercial break because he was very interesting and fascinated by things scientific and astronomy.

[00:14:35] Speaker A: We will come back to the moles because that fascinates me, too.

[00:14:42] Speaker B: Good stuff, man. Can't get away from it. It's everything.

[00:14:48] Speaker A: We have a connection. We have a Zemeckis connection, which there's always been kind of a feeling of family, you having done Roger Rabbit and Bob being one of our executive producers and a mentor.

What was your experience working with Bob, Mike?

[00:15:10] Speaker B: I love Bob Zemeckis.

He's one of the greatest ever. I mean, by back to future, too.

[00:15:18] Speaker A: That's right.

[00:15:19] Speaker B: That's right. Jeez. There's a lot of different things that I work with him. Polar Express.

[00:15:26] Speaker A: Sure, sure.

[00:15:27] Speaker B: Yeah. He's just a great guy and a great artist.

His enthusiasm. And there's, like, some sets you're on and, you know, maybe a grip will have an idea and say, hey, well.

[00:15:42] Speaker A: What if you put.

[00:15:42] Speaker B: If you put that thing over there, I'm Frank Talbot, and you're telling me how to get the fuck off my sack, you know? But if somebody says something to some mechanics, it's a good idea, I go, you know, he's just a beautiful human. Yeah.

[00:15:57] Speaker C: We felt the same way. We worked with him on Tellson the crypt for many years, and it was always a delight. Always great fun.

[00:16:04] Speaker B: Yeah. Great talent and a great person. They don't always come into the same package. You know, some people are really talented, and they just. Their talent maybe overpowers their dignity.

[00:16:15] Speaker A: What was the process like of creating the. Because the voice really comes out of character. The thing about that makes Roger Rabbit really such a great character is that you can feel his soul.

[00:16:28] Speaker B: And so it's the essence of any. Any performance art, you know, or I would say any art, you know, the. Your soul is somehow transmogrified into the medium. It could be, you know, Kandinsky painting or a piece by Mozart or Beethoven's 7th 2nd movement. You know that it's that transfer of soul, but it's.

[00:16:53] Speaker A: But it's easier said than done.

[00:16:56] Speaker B: Well, as is the case, it's easier sold than sold.

[00:17:01] Speaker A: Well, there you go.

[00:17:02] Speaker B: Sure enough, when.

[00:17:06] Speaker A: For us, the Zemeckis experience can be summed up after we had written the script for the yellow episode, when he did his last episode, he asked us to write it for him. And we went up to his place outside of Santa Barbara. God, I hope it's still there. And we had lunch, and after lunch was done, we pushed the trays aside, and he said, guys, all I knew is, for the episode, I want to do a whole show, single camera, from the point of view of a dead guy.

And I want the dead guy to be played by Humphrey Bogart. All right, guys, how are we going to do this? And you were given an impossible assignment. Except it's not impossible because Bob already has some ideas, and he's. You know, you can throw something back at him. That might not work entirely, but you can't throw back a bad idea. And it's that hate. For me, it was the thing that I learned from Phyllis Katz. The improv thing is. Yes.

[00:18:10] Speaker B: And you know, Humphrey Bogart. If you slow Humphrey Bogart down, it becomes more like Boris Darloff.

[00:18:18] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:18:20] Speaker B: Become a Jackie Mason. Jackie Masonde. Become Boris, Carl and Humphrey Bogart. It's all similar.

[00:18:27] Speaker A: It's like Boris Karloff is the touchstone for everybody.

[00:18:30] Speaker B: I don't even know what you're talking about, but I like. And Peter Lorre sneaks into that, too.

Those are the days, huh? Tell you, kids today.

[00:18:42] Speaker A: Yeah, the voices. Well, yeah, they. Because a lot of them still had to live in radio, and they had to. They had. Radio had to be one way that they were going to sell themselves. So your voice. Hey, once talking came the ones who. Who didn't have the vocal cords to.

[00:19:00] Speaker B: Go with the face, you know, I still think the voice, you know, Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, any of those guys, you know, almost any human has a fairly distinctive voice.

And if they do something that's worthy, then you can pick out the high points and, you know, make it into some sort of impression or somehow.

[00:19:20] Speaker A: But what makes for a great actor or even a Churchill is that they learn how to use that voice.

[00:19:25] Speaker B: Right.

Who, you know, always does, you know, different voices. He's a chameleon.

[00:19:33] Speaker A: What was the first voice you ever did, looking back as a baby?

[00:19:39] Speaker B: I think it was just the umbilical screams of madness.

[00:19:42] Speaker A: Well, there you go. So.

[00:19:46] Speaker B: The first voice, on a professional level, I would have to be, oh, Roger Rabbit, I think maybe. Yeah, I think it was Roger Rabbit. Although, thinking back, Wes Craven, I was in Amaranth street, but I did a thing called deadly friend, which was about this robot, a robot rowboat, and it had to have a voice. And I think I even had a kind of effect before Roger occurred. So that could have been the first.

But obviously, Roger Rabbit was the most of all.

[00:20:29] Speaker A: What, where. Where did that particular voice come from?

[00:20:33] Speaker B: I would say Midwest, about 430. Well, like any, any character that you portray, you have what's written in the script, and that brings on something. But in addition to that, there was his physical characteristics. So had he been, you know, very small, that voice wouldn't have worked, and really big. So you have to make the voice sound like it would emanate from that kind of a chamber. And, you know, you search and you come up with something, I think.

[00:21:07] Speaker A: So you start by trying to physicalize what. What the physical would sound like.

[00:21:12] Speaker B: Yeah. Just sort of like, do it. Let's see. John Houston was kind of. I had, like, shake little John Houston in it somewhere.

You know, it just all kind of came together somehow.

[00:21:29] Speaker A: It was.

It's. It's such a lovely La Noire story.

[00:21:36] Speaker B: It's La Laws.

[00:21:38] Speaker A: Did you say a lovely La Noire story?

[00:21:42] Speaker B: Oh, la noire.

[00:21:43] Speaker A: La noire.

[00:21:44] Speaker B: I know a girl named Elie Noir, and it's like, boy, share stories. Weren't that lovely, but she was good looking.

Elie Noir.

[00:21:54] Speaker A: The science paper that, that you wrote, when did you first.

When did you first start thinking about gamma reverse?

The mole? The Moleads?

[00:22:07] Speaker B: Oh, Molly's is way before gamma burst moleads.

Around my 27th birthday.

[00:22:15] Speaker A: Yeah, that. It goes. It goes way, way back in your thinking.

[00:22:18] Speaker B: Yeah. That's because my mother had given me a calculator as a present, and I was playing around on that, and then I started seeing these patterns, and then, then that just went on and on and on.

[00:22:32] Speaker A: What pattern did you see that sparked this?

[00:22:37] Speaker B: One divided by three. That divided by three, then that divided by three. And it was 0.027,027, because three to the third power, zero, three, seven. So one divided by 27 is 0.037 and vice versa. And now it's, you know, I have, you know, 30 years or more of research on it. And basically what Molly's does, it allows you to see that any prime number will generate a system of numbers, which is the prime minus one.

That go together into pairs that add to the prime number. So, for instance, in Molis, it's 37 is a number. So one and 36, 37, two and 35, three and 34. So there's 18 pairs of numbers that add to 37. That's true for any prime number. So moleads is directly related to prime numbers, which is intrinsic and a lot of mathematical understanding. The gamma ray burst, which could have began with. I was just googling around, looking for different palette ideas to use for watercolor, different spectrums that you can use to do watercolor painting. Like, there's, like, you know, a renaissance palette that's more kind of amber tones. And I came across this one image of a gamma ray burst, and the spectral effects that it caused, and it just, like, struck me, just started being fascinated. Were these gamma ray bursts, the explosions that are the largest display of energy in the universe, and they don't really know what they are. And just to me, it just seemed like this is. It just struck me. It hit me. It resonated.

[00:24:26] Speaker A: Yeah.

Literally, figuratively and otherwise.

[00:24:30] Speaker B: Metaphorically and that too manically. What rodeo?

[00:24:38] Speaker A: What? What does this say to you? This.

What's at the heart of it?

[00:24:45] Speaker B: All of the gamma ray burst or the heart. Well, the heart of all of it.

[00:24:49] Speaker A: All right, so the gamma ray burst. Yes. So there's energy flying around. There's light. There's.

But, all right, you have discerned a pattern that other people hadn't, but you saw a fascinating pattern. And the way that you've broken down all the different colors and the way that. Yeah, the way that they break down into shapes. There's something. There's something.

[00:25:17] Speaker B: Well, yeah, the current theory is that they're random. And the essence of my paper was that they're not random.

And my hypothesis was that it represents some kind of communication.

It's a hypothesis. I can't prove it at this point, but, I mean, it's conceivable it could be something that's unknown that's causing this, some space worm farts and a Ydezenhe distant galaxy, and that causes something to happen. But, you know, for me, it makes sense that it is some kind of a communication, because if you were a highly advanced organism, you want to talk about it. You know, just. It's all to impress the girls, basically.

[00:26:02] Speaker A: Isn't that always the way some laws are universal? Apparently, yes.

[00:26:07] Speaker B: The way it works, you know, like, you know, for a guy, you know, it's like Orlando or press the guy. Press someone that you want to love you, whether it be man, woman, antibiotic, whatever. But you know, you demonstrate that if you're a bowerbird, you build nests or something. If you're a kite bird, you steal pieces of white plastic and put it in your nest. If you're a scientist, you may. Honey, I think I did it. Oh, Felix, take out the trash.

[00:26:39] Speaker A: You think you're so special.

[00:26:41] Speaker B: So, yeah, that's the essence of that. And the underlying essence, I think, of all of it and all the science is to find something that is not yet established, something that's there but not known. For instance, golden ratio, which is a mathematical proportion. I think that's probably the greatest aspect of science that's known but not fully realized.

[00:27:07] Speaker A: What do you mean by that?

[00:27:10] Speaker B: Well, I think that the way that so many things in the universe have golden ratio of proportion. The galaxies, the logarithmic spiral, the shape of an object determines the behavior of things in it. For instance, the shape of a tuba determines the sound that's emanating. So the shape of our universe determines behavior of things within it. So that's the universe.

[00:27:37] Speaker A: The shape of it being like the way that it's assumed with it's from the big bang emanating outward like that.

[00:27:44] Speaker B: Well, and also part of it, there's one scientist named Luminet, he's a french astrophysicist who found that there were indications that the universe had a shape that would be kind of like a dodecahedron.

So most scientists think the universe is flat, which seems like, I guess, but it makes sense to me that it would, that it could have a shape. If it did, if it was shaped like a dodecahedron, then that may explain why there's the proliferation of golden ratio everywhere. I mean, your fingers, the vertebrae, it's just, it's a magical number.

Not that pie isn't. I love pie, too, just for the reference. You gotta love pie. And just the fact that they, you know, they go on their irrational numbers, which sounds irrational, but, you know, they just keep going. That to me is like, well, there's so many clues, you know, left behind that indicate that we're involved in something that is not fully known.

And it's our job to figure out what. You can put it on the table so the next generation that comes along can like, look on a table and go try one of these. Oh, look at that. And then, you know what Newton, I think, said, standing on the shoulders of giants.

[00:29:11] Speaker A: Indeed, if the universe could reveal just one, one of its secrets, which one would you want to know?

[00:29:21] Speaker B: Well, if it's a secret I probably shouldn't say.

Oh, geez, that would be good.

[00:29:27] Speaker A: Only because we haven't unlocked it yet.

[00:29:29] Speaker B: I'd like to know about the beginning of it, before this one began, the whole big bang thing. And if it parallels other things, maybe it's possible that two universes got together and boom. And made this one. Most life comes about by combining two life forms to create a new one.

That's a hypothesis. Who knows what will happen when this one ends? Where do black holes go?

I'm pretty convinced that this universe is finite, but there are an infinite number of finite universes more mind boggling than just one infinite universe, because infinity, for my money, deals with quantity. Like, you know, PI goes on infinitely. But when you get to size, I don't think things are infinite in size. I think there's restrictions based on laws of physics.

You can always get a number and just go add one to that.

Nope. Add one more.

That's pretty. Pretty sobering.

[00:30:47] Speaker A: Do you imagine there is an end of time?

[00:30:52] Speaker B: Well, in what capacity?

You know, like your personal time.

[00:31:01] Speaker A: Well, we all, unfortunately, our time on the planet here in whatever this is, is finite.

[00:31:09] Speaker B: Yeah. All of us.

Well, if there's an end, they'll be a beginning, because the beginning of the end is the end of the beginning.

[00:31:21] Speaker A: That's what I'm rooting for.

[00:31:23] Speaker B: You know, it really doesn't even matter because, you know, if you have good seats, just enjoy the show, and if you don't, an intermission move down and take the ones that were vacant.

[00:31:36] Speaker A: How long have you been painting?

[00:31:39] Speaker B: I've been expressing myself visually pretty much my whole life. In college, I remember when they were having a lecture, something, and taking notes and drawing on my notebook. And when it came time for the midterm exam, I could look at my notes and, oh, the mouse wearing the space helmet jumping over the car. They were talking about ribosomes there. When it came time to finals, what the fuck? Have a mouse and a hat. I don't know what that is.

So I've always loved that. I've always been inspired by people like Salvador Dali or Mc Escher or Gilles Bruvel or anybody.

[00:32:19] Speaker A: Have you ever tried to express these ideas of infinity in your art?

[00:32:27] Speaker B: Yeah, I've done some pieces that speak to that concept, you know, little perspective does that.

[00:32:34] Speaker A: I hope you don't mind. I'd love to put a couple of. Just link to it, just a couple of your pieces up.

[00:32:40] Speaker B: No, I wouldn't mind at all.

[00:32:42] Speaker A: I gotta tell you, man, I did not know that Charlie was an artist. I am blown away by his stuff. It is phenomenal. It is. And it. And it's varied. You have a bunch of different styles.

There's. There's some stuff that. That's. That's Magritte. There's. There's touches of man Ray here and there. There's Escher.

[00:33:06] Speaker B: Different mediums. I like, like digital. I like using pen and ink. I like mixed media, watercolor, you know, anything as long it's. You know, it goes back to storytelling.

[00:33:19] Speaker A: There's.

[00:33:19] Speaker B: There's one that I think you guys do.

[00:33:21] Speaker A: Yeah.

There's one I mentioned called the rhythmic shimmer of glimmer waves that. I think it's just, I I find myself going back to it constantly. There's the light in the background that kind of.

I love that it silhouettes the two women walking through that light. It's fantastic. It's.

[00:33:42] Speaker B: I tried to also incorporate titles that are poetic unto themselves.

[00:33:49] Speaker A: That was my next.

[00:33:50] Speaker B: That's my next question directly to the picture. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Like the museum of self reflection. Reflection.

[00:33:56] Speaker A: That one, I totally.

The rhythmic shimmer of glimmer waves. And we will put that one up so that if you're. If you're at our website, you can see it. It's great. Great piece. Definitely worth a. $100 for a print. My God, what, are you giving them away, man?

[00:34:13] Speaker B: Well, I thought of that, but then I decided, you know, for printing costs, I'll color myself.

[00:34:18] Speaker A: I'm also fascinated that there's, like, Monroe boat. Uh, she is surrounded by. By the colors.

[00:34:28] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:34:28] Speaker A: By the circle of colors.

[00:34:30] Speaker B: Non robo. Yeah. I also have one with, uh, Zappa. Zappa. Yeah.

[00:34:35] Speaker A: Yeah, zappa.

[00:34:36] Speaker B: Also Picasso as well.

[00:34:37] Speaker A: And Picasso also surrounded by. By the colors.

Uh, is this just a coincidence that, you know, your. Your. Your color wheel from. From the Maldives and. And. And these pores?

[00:34:48] Speaker B: Well, you know, colors are just part of the electromagnetic spectrum that we see, visible light.

And it's just a way of combining ink drawing with something that's colorful and three dimensional, and just. You get ideas where they come from, and I think that's what drives any person that creates, whether it's visual or audio or just push it.

[00:35:17] Speaker A: Another piece that I love, and I'd love to know where the damn title came from. Jade raccoons, frightened cotton, mice.

It is a landscape, really. Half and half, sky and flat like a desert. Gray, but reflective. Like it's wet.

[00:35:38] Speaker B: Is there a red chair?

[00:35:40] Speaker A: There's a chair in the middle of it.

[00:35:42] Speaker B: Yeah, the red chair. Yeah.

[00:35:44] Speaker A: Jade Raccoon's.

[00:35:45] Speaker B: Frightened of.

[00:35:47] Speaker A: Yeah. Jade. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Jade. Raccoons. Frightened cotton, mice. Thank you.

[00:35:52] Speaker B: Yeah. Jacqueline? Well, um, you can see right back there, I have a red chair. See, right there? Yeah, yeah. Well, after I did the museum of self reflection, which is a museum, and in the museum, there are paintings. And the paintings in the paintings have paintings in the paintings.

[00:36:11] Speaker A: Oh, that's so cool.

[00:36:12] Speaker B: That took over three years. So after that, I was looking for something that wouldn't take three years, and Salvador Dali already had a melting clock, so I thought about why. What about a chair?

Take a chair, and you put it in the middle of nowhere. A chair, huh? Is anyone sitting in the chair? No, just an empty chair. What color? A green. I tried green, but it blends. We see more shades of green than any other color. Make it a red chair, it'll stand out more. Okay, so I have a whole series of the red chair. Series of just one red chair in the middle of nowhere.

[00:36:49] Speaker A: Okay, so a print costs $100. What. What does the actual. Actual hanging, the artwork itself cost these days?

[00:36:58] Speaker B: Hanging? You mean having it framed?

[00:37:00] Speaker A: Well, no, I mean, but, you know, there's an original. There's an original. This is coming from, isn't there?

[00:37:07] Speaker B: Some of them have analog originals. Others of them were created in the digital realm.

[00:37:14] Speaker A: Gotcha. So it is entirely digital, and so there is no singular analog.

[00:37:20] Speaker B: Well, for some of them, yeah. Like the ink ones, you can pretty see. And there's some.

[00:37:26] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Okay.

[00:37:27] Speaker B: There's a way of categorizing, like, old school, new school, etcetera. And the old school stuff is definitely, you know, you can see that it's analog, and some of the new school stuff is. Is all generated digitally. But any of those digital works I could transfer to canvas and have it be.

Exist in that space?

[00:37:52] Speaker A: Sure, sure. The rhythmic shimmer of glimmer waves, that that's. That's actual, or is that digital?

[00:37:59] Speaker B: That's combination.

[00:38:03] Speaker A: I am so fascinated, I can't tell you.

[00:38:07] Speaker B: And I don't mind that a fascinating person is always fascinating, you know, if as much as a rhythmic person is rhythm.

[00:38:13] Speaker A: And I got to tell you something, Charlie. If Gil and I can sell this show, we're literally about to go out with, not only am I. Am I going to buy a bunch of these prints or even going to hire you, man, if you can sell the show.

[00:38:25] Speaker B: Let's go back a step.

[00:38:26] Speaker A: Well, come on, come on, come on. With a grain of salt.

[00:38:30] Speaker B: When Gil and I sell this show.

[00:38:32] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:38:33] Speaker B: If we find someone, do we want to sell to me. May not even want it. We got six office. I don't want to sell it.

[00:38:39] Speaker A: But first I'm going to buy a couple of these prints. That's much more important to me than anything. Never mind.

I'm enthralled with them.

[00:38:47] Speaker B: I'm happy to provide people's walls with coverings, but I. Most of the art that I've sold has been after I do a show, because there's, you know, doing my show comedy, and that creates a bond with people. And then once they've established that, then the art supports that connection.

If you just looking around. Oh, that was nice. I mean, I'm sure there's a lot of other artists that are more accomplished in their statements, but my work is. It's a combination of all my different efforts.

[00:39:33] Speaker A: Hey, I'm just one more guy walking into a gallery, and I'm.

[00:39:39] Speaker B: It's better than me. I'm one more guy walking into a wall.

[00:39:41] Speaker A: There you go. Well, that's.

[00:39:43] Speaker B: Walked into that one.

[00:39:44] Speaker A: That's. Afterwards.

You also do music.

[00:39:52] Speaker B: Yeah, actually, earlier, when I said the beginning of the end is end of the beginning, that's from a song that I wrote.

It's probably on Spotify or something.

Yeah. I love music. Anything that has touched my soul, whether it be art, music, like that experience that I got when I first heard Jimi Hendrix or when I first saw Salvador Ali, that was so exciting to me. I wanted to be able to, like, I want to do that for somebody else. I want to, like, take that and, you know, push my soul dream in their direction and see if it, you know, it catches on and makes them do something.

[00:40:34] Speaker A: Who are you listening to right now that really excites you?

[00:40:38] Speaker B: Oh, gee. I mean, I listen to a lot of Hans Zimmer, but that's when I'm writing. I like to listen a lot of this stuff. I was listening to smashing pumpkins all day long, listening to adore, which goes back to 1998.

But I really liked that album.

[00:41:04] Speaker A: You said while writing, you listen to music while writing. And one of the things that I also want to touch upon is you've just finished a collection of short stories.

[00:41:14] Speaker B: Well, it's not. If it was finished, it would be out, so it's not out yet, but it's. It's close to that point. Okay. Yeah. Called out of my mind.

[00:41:26] Speaker A: And this is, you know, yes, you've been writing your whole life, but this is. This is. How many stories are in the collection?

[00:41:34] Speaker B: This is ten.

[00:41:36] Speaker A: How long has it taken you to.

[00:41:37] Speaker B: Tales with thunderbolt twists.

And I think of all the things that I've done, this is the most me, that thing, whatever I am, this is the purest form of that.

[00:41:53] Speaker A: Why do you say that?

[00:41:56] Speaker B: Because it's the truth, brother. Because it's. Writing is so personal and combines so many different valiant efforts. You know, just getting an idea for a story and then constructing the story and then, you know, that's like a blueprint. And then the actual building of it. Each. Each piece of lumber is cents. And then the nails and just, you know, that sentence is not good, that people don't talk like that. And then just, you know, they're writing and they're rewriting. But then once you do actually lock something in, then that's really empowering. And then, you know, you keep building on that. And then I.

It's. I think it's a magical, magical situation to be able to.

[00:42:41] Speaker A: Is it ever really done, though?

[00:42:44] Speaker B: Yeah, I think so.

[00:42:45] Speaker A: Is it? Oh, my God. You are. I wish. I wish I had. I wish I had that button. I wish I had that button.

[00:42:52] Speaker B: Oh, yeah. I think it is. I mean, there have been times with my artwork where I just kept going, especially when I'm just doing something in a sketchbook. And, you know, I get to the point where it's like, wow, I think I messed this one up. That's why I liked moving into a digital realm, because I could do something and save it, and then I could just keep messing around. But I still had that one over there. And out of, like, the messing around stuff I like, maybe I get a seed of what will become another new one.

But I think with stories, you know, you get your beginning, middle, and end, not all ties together, and then, well.

[00:43:30] Speaker A: You know, what you just touched on was really interesting because, really, it's the form that. All right, whatever the creative form, if you are creating in the visual form that's working digitally versus working with actual material, do you find there's a difference in the kind of things you create when working with one medium versus the other?

The medium partially dictates what will come.

[00:44:01] Speaker B: Out of you to an extent. You have to work within the parameters of the medium you choose, but it does essentially go back to storytelling. I mean, you know, some people might say digital art, you didn't do that. Computer did it. Or when people started using brushes and paints and tubes, you know, came in go that not artist handed, whoa. Printhead. So it doesn't matter. Pencil doesn't matter what you use, as long as you get it out. It tells a story, if it communicates something, if it is capable of touching somebody else's soul, then that. Then it's a win.

But that's why I go to different medias, because it will allow another current to flow into the bucket.

[00:44:49] Speaker A: Some stories require one form versus another.

[00:44:53] Speaker B: Yeah, I think so. But as, essentially, it's the story, but, yeah, when I'm working on my sketchbook, it's. I usually work in increments. I'll, like, do a little bit and then go to the next page and then work a little on that depends, you know, and there's some that are all planned out because it comes from an older sketchbook and some that I'm just, you know, looking to find something.

[00:45:18] Speaker A: Most of your life now is taken up with art, so.

[00:45:24] Speaker B: Always been that way. Some kind of art.

[00:45:26] Speaker A: Yeah, but is there. Is there one of you? Is there one art form that's getting more of your attention these days?

[00:45:35] Speaker B: Well, these days I'm finishing up this writing, but, you know, I love all these things, you know, but the thing about acting or doing stand up, that requires a venue, a producer script. It's. It requires other people saying, yeah, so if that is not making itself available in a way that suits your parameters, then, you know, you can just sit down and write something or sit down and draw something.

[00:46:12] Speaker A: It's good to be a self starter.

[00:46:13] Speaker B: Yeah, it doesn't.

No one else can mess with you, you know, because now we don't like it. We're not making this movie. It's okay. It's gonna be a book. All right. Take a fork and leak, shanky.

[00:46:24] Speaker A: It kind of goes back to what we were talking about at the beginning, that we get to do this in this format. Podcasting is a kind of. Well, it's radio, frankly, but it's an exquisite kind of storytelling, because, really, you can put together such interesting stories so quickly. For instance, what we pull together here, and you never know, as you start the ball rolling, when you get talking, what stories will happen. You get three people.

[00:46:56] Speaker B: Joe Rogan started doing this right, and he's now, you know, probably the biggest podcaster, if you still call it that. You know, tv, whatever you want to call it. You know, the field is open.

[00:47:12] Speaker A: It's very democratic.

You know, you can. Well, it's diy. It's entirely diy. And getting an audience. Okay, that's. That's where the. The real heavy lifting has to come in. But I. But the first goal is always, as an artist, is to create honest content or dishonest content.

[00:47:35] Speaker B: If that's what's selling, hey, so long.

[00:47:38] Speaker A: As you're honest about it, that's as.

[00:47:40] Speaker B: Long as you're content with the content and you think that you won't resent, then you present what you invent and the content will pay the rent.

[00:47:49] Speaker A: Exactly. Don't be acting like it's the exact opposite that. No, that's what I meant to do.

[00:47:54] Speaker B: I could tell. You stimulated me and I elated my stimuloid.

[00:47:59] Speaker A: Thank you.

And on that note, having stimulated your stimuloid, what remains undone for you, Charlie, as you look at all the creative stuff that you've done, I think that.

[00:48:18] Speaker B: If I knew that, it wouldn't be undone, so.

But I'm confident that there is a realm of materials that I have yet to bring into focus.

[00:48:33] Speaker A: For instance, like when you say materials.

[00:48:36] Speaker B: Well, materials available, constructs that can be purposed into something beautiful create beauty. Truth is beauty, Keats. Beauty is truth. Just, you know, make things that inspire people, touch people, leave work behind that will touch some kid who hasn't been born yet.

You know, the same way that, you know, reading the work of great people, you know, inspired me to do certain things or to. Or to take a jump in a certain direction, you know, just pushing the whole ball forward. We're all part of this.

[00:49:22] Speaker A: You are. It's funny. You have a character, Roger Rabbit, who is willing to do her for the ages.

Most likely it's that kind of character.

[00:49:32] Speaker B: I mean, it's a, it's a classic film. It's a. It still holds up.

[00:49:36] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. We'll be talking about that a long, long time from now. They.

[00:49:41] Speaker B: And, you know, I was also Benny the cab and two of the weasels.

[00:49:52] Speaker A: How do you.

Well, what does that feel like, really, is the question.

It's got to feel great to having that. Nevermind on your bio, but it's as part of your story, part of it's.

[00:50:05] Speaker B: Good, but it's, once you've accomplished something, you've accomplished it and you're looking forward. But also, do you see the movie Zodiac, David Fincher?

[00:50:15] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:50:17] Speaker B: That's, I think, my best on camera work.

[00:50:19] Speaker A: Sure, sure.

[00:50:20] Speaker B: And in that, besides playing that creepy character, I was also the voice of a mental patient that calls in to the teaser that Melvin Belli is on.

[00:50:31] Speaker A: As I sat here remembering the movie. You just creep me out.

You were very good. You were very good.

[00:50:40] Speaker B: I do all the posters.

[00:50:41] Speaker A: Yeah.

It's funny.

I hope there is work of that kind in your future.

[00:50:52] Speaker B: There should be Jake Gyllenhaal I knew when he was a little kid, he went to school with my kids. And I remember seeing him in a play. I think it was grease, but it was about grease, not the, you know, not the musical. And, you know, I said, wow, this kid's really talented. And his mother is a writer. She wrote the movie running and empty. His father is director, of course. His sister is an actress. Really talented, family. Nice guy, Jake Gyllenhaal, you know what I'm saying? Like, he needs me to talk about him. Oh, boy. Thank God. Shall he mention me? Maybe I got a shot now.

[00:51:33] Speaker A: Hey, you know, one of the things is when. When Gil and I go about promoting our podcast, and it's an everyday, you have to do it every goddamn day. And what you have to remind yourself is that you know what Coca Cola is, and Gil knows what coke is, and I know what Coca Cola is. We all know what it is. We all know where it is and where to find it and when to drink it. And yet the Coca Cola company still feels compelled to advertise what it is and where to find it every damned day.

You have to.

[00:52:07] Speaker B: You have to.

[00:52:08] Speaker A: You've got to promote yourself.

[00:52:09] Speaker B: Aren't there some companies that don't advertise at all?

[00:52:13] Speaker A: Trader Joe's is kind of minimalist. They do a little bit of advertising. There are a couple of companies that. Oh, there's one. It'll come to me. Yeah. That. That are somewhat famous for never, ever having done it.

[00:52:27] Speaker B: You know, the classic Coke story where, you know, it only used to be in soda fountains, right? And some guy came along and said, maybe if you put it into a bottle, sell the bottle.

But I haven't had that beverage or any kind of soda pop of, you know, I try and maintain a healthy perspective on freshness and, you know, a lack of chemicals, things that weren't here 300 years ago, you know, the greed. Because a lot of the food companies, they were tobacco companies, and they just put all the stuff into the. And to the food, and, you know, it's just greed.

[00:53:14] Speaker A: You know, if we could cure the greed, if we could cull the green, the gree gene out of the human genome, oh, what a fantastic creature we might become.

[00:53:26] Speaker B: Well, you know, that diversity keeps it going. You know, that's the way nature seems to work. There's always, like, a balance to maintain that if it gets all over here, even if it's all good, that what's going to check that before the good becomes the bad. So there should always be a balance.

[00:53:43] Speaker A: I got one last question for you, Charlie. This has been. Thank you so much for doing this with us. My last question is, are you hopeful for the future?

[00:53:52] Speaker B: Of course I'm hoping for the past.

That's a hopeful? I am. That's another kind of hope. Hoping for the future? Sure. It's yet to be, but when you're hoping for the past, that indicates you might know something.

[00:54:06] Speaker A: I worry about people who are hopeful for the past because they're so nostalgic for it.

[00:54:11] Speaker B: Well, hopeful and nostalgia are different issues. I suspect nostalgia is kind of almost leading towards a morose reminiscence. However, hopefully implies that you're aware of other timelines, of other ways that things can move forward or backwards.

[00:54:32] Speaker A: I've always heard great things about the future.

[00:54:36] Speaker B: Well, it usually comes from the past.

[00:54:40] Speaker A: It certainly has got to flow from somewhere in the stream of the time space continuum.

[00:54:47] Speaker B: Yeah, well, the future doesn't ever really exist. It's always now. Okay, here's a question for you to wrap things up for you. There you go. Okay. We're always in the now, right? So that means that this database that is the past is continually getting bigger because everything is happening is flowing into that. When I started this statement, that's on the past now. So the hypothetical thing we call the future as the past is getting bigger, what's happening to the future? That's my question to you. There's no way to prove it. What do you suspect?

[00:55:21] Speaker A: It's infinite.

The future is infinite.

And we. And we bottling it. We end up containing it.

[00:55:32] Speaker B: But the past is getting bigger.

[00:55:34] Speaker A: Ah, it's a big container.

[00:55:38] Speaker B: I'll give you three choices. It's staying the same. It's getting smaller, or it's getting bigger.

[00:55:46] Speaker A: The future? Are you referring to.

[00:55:48] Speaker B: Yeah, as the past is continuously getting bigger. What's happening to the future in your humble, less timoit.

[00:55:55] Speaker A: And it's a fascinating question.

[00:56:01] Speaker B: Deserves a fascinating.

[00:56:02] Speaker A: It's. It's the same. It's. It's always the same.

[00:56:05] Speaker B: As what?

Okay, I'll give you what.

[00:56:07] Speaker A: It's what it always was. It is unchanged.

[00:56:11] Speaker B: As the past is getting bigger, so is the future, which implies that the potentialities of things in the future are growing at the same rate the past is. Which explains maybe, like, why you think, like, you know, how come I never thought of this before? Because the possibility of that idea had not congrued in this database. That is the growing future. So as this past gets bigger, the future does as well, because it bounces out so that the more time flows, the. The greater the possibilities to grab from the future and bring them into now so that they can become the past.

[00:56:51] Speaker A: Is. Is there a paper in this?

[00:56:53] Speaker B: Uh, that's not even worth the paper. It's.

[00:56:56] Speaker A: Oh, damn.

[00:56:58] Speaker B: It's a gun wrap. There goes.

[00:57:00] Speaker A: There goes that sideline.

[00:57:02] Speaker B: If you get to the point where it's, uh, empirical formulas, you know, you could. But who would read it? Because the point would be, like, by the time they read it would be the past and the future would already have a better paper ready.

[00:57:13] Speaker A: I think it would depend how funny we could make it.

[00:57:16] Speaker B: That's always an issue.

[00:57:17] Speaker A: There you go. And it's so funny.

[00:57:19] Speaker B: Can change too. I mean, look at jokes that people were telling 20 years ago, and now they're, like, getting booed for. So the dynamic is always shifting.

[00:57:29] Speaker A: Indeed it is. Forever shifting.

[00:57:33] Speaker B: Yeah. That's why sometimes you just have to shift yourself.

[00:57:37] Speaker A: What else can you do?

[00:57:39] Speaker B: But don't be too shifty.

[00:57:42] Speaker A: That's the risk.

Successive shiftiness.

Again, we thank you so much, Charlie, for joining us in this little misadventure of ours.

[00:57:54] Speaker B: Did you say misadventure?

[00:57:55] Speaker A: I said misadventure of ours.

[00:57:56] Speaker B: Yes.

[00:57:56] Speaker A: This is a misadventure of ours.

[00:57:58] Speaker B: I think it more as a myth invention.

[00:58:01] Speaker A: That too. That too.

[00:58:03] Speaker B: I like mythology.

I think we can create our own mythology.

[00:58:10] Speaker A: Oh, hey, that is. That's. That's the job. Because if you don't create it, someone's going to create it for you. You don't want that.

[00:58:19] Speaker B: Or, you know, an AI can create it for you and me, you know, and this is not my joke, but AI, they can, you know, they can make an incredible painting, but only a real artist can go to Berlin and overdose.

[00:58:39] Speaker A: And that's why we'll always be a step ahead.

[00:58:42] Speaker B: That's not my joke. Just want to make that clear.

[00:58:44] Speaker A: But it's. But it's a good one.

[00:58:48] Speaker B: It's substantial in a way that has resonance.

[00:58:52] Speaker A: It definitely resonates.

[00:58:53] Speaker B: I'm doing my resonance at the theater across the street now. It's resonance. No, it's resonance if it rings a bell.

Tintin tibulation. Nevermind. Well, anyway, hey, Mister Poe, and thank you both for including me in this presentation. It was definitely more of a tale than it was a crypt.

[00:59:16] Speaker A: The admission accomplished, indeed.

[00:59:19] Speaker B: No reference to that guy, either of them.

[00:59:25] Speaker A: Neither one of those bastards.

[00:59:27] Speaker B: Go back to the show.

[00:59:31] Speaker A: Don't get us started.

We'll see you next time, everybody.

The how not to make a movie podcast is executive produced by me, Alan Katz, by Gil Adlerez, by Jason Stein. Our artwork was done by the amazing Jody Webster and Jason. Jody, along with Mando, are all the hosts of the fun and informative dads from the Crypt podcast. Follow them for what my old pal the crypt keeper would have called terrific crypt content.

The Rhythmnic shimmer Of Glimmer Waves

The Rhythmnic shimmer Of Glimmer Waves

Museum Of Self Reflection

Museum Of Self Reflection

Monroe Boat

Monroe Boat